09/23/14 Using Stacking for better Night Photography results

I have found that working at night in Arkansas can bring out some amazing photographic opportunities, like the photograph below.

Since early in 2008 I have been fascinated by one facet of night photography—the creation of star trail photographs. Capturing the motion of the earth over a period of time and blending the light of the distant stars into different lines of varying brightness is my mission. My first attempts consisted of just leaving the shutter open over a period of time and varying it from 30 minutes to 1 and half hours. My initial thoughts were that the best conditions for shooting the stars would be nights with little or no moonlight. The results in my location (Arkansas), were a bit disappointing since the ambient light from nearby towns and even a single home would give the sky a yellow/orange color. If I tried to change this yellow sky color in post processing it also influenced the color of the star trails making them red/yellow.

In this image, you can see an example of how light pollution can totally turn the night sky yellow/amber and the non-sky parts of the image have no details. Attempting to pull up the foreground produces a noisy and non-detailed image.

Things changed for me quite by accident as one night I was out when there was a half moon. The results from this short 20 minute exposure with moonlight moved things in a totally different direction for me. Instead of the yellow/orange sky, I now had a beautiful blue hue, with pure white star trails. Even more impressive was just how much the surrounding landscape had been illuminated. Now instead of a dark silhouette I could now see most of the details of the landscape. The colors all had a naturally strong saturated look and I was hooked. However after a few months of shooting in this mode, I noticed that as my single exposures approached 40 minutes the trails started to become faint to a point where only the strongest stars continued to show trails.

This is a 45 minute single exposure from a Phase One P45+. There is a good balance however only the strongest stars are showing through. There is considerable wind blur on the trees along the bluff.

If I tried to pull the exposure of the sky down, I lost many of the faint trails. I tried a few different solutions with filters, but nothing seemed to really give me the sky that I was looking for, one with a nice deep blue hue and filled with star trails. Then I read about some photographers that were stacking their exposures and I became very interested in what my results might be from night exposure stacking.

This is a 1 hour exposure taken in approximately 2 minutes stacked exposures. Notice the vastly greater number of star trails and the lack of motion blur.

The idea of stacking comes from photographers working with time lapse capture. The idea is simple enough, instead of one long single exposure, take a series of short exposures and then blend them together in Photoshop. By using Photoshop I found that you can create a smart object from all the stacked exposures and then run a series of blending modes on the smart object that capture only the movement of the stars in the night sky, creating the trails. Each night the period of time of each exposure will vary and it takes a few attempts to get just the right time for the best segment. Ideally I can find an exposure/aperture combination that shows bright stars but also allows for illumination of my landscape features. Since most exposures will be longer than 30 seconds, you need an intervalometer. With the intervalometer, set the interval to 1 and then set the total time of each single exposure. Then set the camera to continuous mode and for blub exposure. For example, if your exposure time for each segment is 2 minutes and 30 seconds, for a 2 hour exposure you will take 52 individual images to stack together later.

Stacking has several advantages over a single long exposure:

1. You have more interesting subject matter overall

- Since you now have the ability to see the landscape subjects that are illuminated by the moonlight, you have a much more interesting photograph. The illumination provided by the moon can be quite eerie at times and offers a unique look to the final photograph.

2. The ability to handle wind motion:

- During single long exposures, more than likely you will have some wind. The wind over a period of 2 hours can totally blur your trees to the point that it will actually ruin the photograph.

- Stacking allows you to find the best single exposure of the foreground and layer it back to the final image.

3. Hundreds of distant stars are brought into view:

- With night photography, you will get more distant stars the wider you can open the aperture so ideally you would try to work with aperture ranges of F2.0 to F4. Any wider and you will start to run into DOF issues with most lenses. Stacking allows you to work with these wider apertures. In contrast, working at F2.8 to F4 with a single long exposure of 1 hour most likely will cause the sky and stars to be overexposed.

4. Much more flexible workflow:

- Since you are stacking you will have many different images to work with in your landscape portion of the image. You may want to pick several and blend them together to take the best parts of each. You also may want to experiment with light painting on one segment. If it doesn’t work out, you don’t have to use that part of the stack, however if you light paint on a single long exposure and make a mistake, then you have ruined the entire sequence.

This is a 35 minute single exposure where no moonlight illumination was used. The combined light painting still really did not begin to pull out the details of the tress along the bank and the light painting only provides a 1 dimensional form of illumination.

5. Better control over plane trails:

- I have yet to work a night where planes did not fly over. If you are stacking, you can take out the plane trails before you run the blending modes to combine the images. Plane trails will always be some form of a straight line and will contrast sharply with the curved star trails in the night sky of your image.

6. Noise of a single long exposure vs stacking multiple exposures:

- Over the time of a single long exposure you can expect your camera to generate quite a bit of heat and thus get excessive noise and stuck pixels. If you stack, the shorter exposure times will contain less noise and fewer stuck pixels. This can make a big difference in the final image.

My current camera selections are the Nikon D800E with the 14-24 F2.8 lens and the Canon 6D with the 16-35 F2.8 lens. Both of these cameras allow you to turn off the long exposure noise reduction, which is critical. If you leave it on, then you will have a mandatory dark frame between each segment, which creates gapping. For both of these cameras, I use the accessory grips with extra batteries so I can get the longest operating times from each camera. I use a wired intervalometer with each camera to control the exposures. My goal for night photography is to maximize my sky view so I tend to work with focal length ranges of 14mm to 20mm. For the night exposures, I set the white balance to around 4330K.

For this night work, I like to shoot raw files as I feel you have more control over the file in post processing than with a jpg. I will then take 5 or 6 images from a series and work them up in both Lightroom and Capture 1 to see which software seems to handle the series better. On a 2 hour series, you will have to make some minor adjustments to the images to help balance out the sky illumination, since the motion of the moon will change the color of the night sky over time.

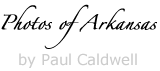

Once all the images are worked up, I will export them as 8 bit tiffs. I have found that the 8 bit quality is more than enough for the images I am creating. I will load the files into Photoshop layers from Photoshop Bridge, then select all the layers and create a smart object. This process may take a while with 52 tiffs especially with a series of 36MP images. Once the smart object is created, I recommend to save it, in a large document format with a .psb extension as odds are the file will be larger than 2GB in size. Then you can run the stack modes on the smart object.

This is a screen shot from Photoshop. All the individual images have been loaded into Photoshop as layers and the stack is now ready to be turned into a smart object.

The stack blending modes are now part of Adobe CC and CS6. If you have an earlier version of Photoshop you will need to download them from the Dr. Brown website (www.Adobe.com). I like to run the Maximum and Mean modes and save the results. Maximum gives you the greatest amount of light to the stars but may be a bit too much, so by running the mean mode, you can layer the two and blend back to a good balance of the sky and stars. The mean stacking mode will also contain less noise.

Once the smart object has been created, you are ready to run the various blending modes on it. In this screen shot, I am about to run the “Maximum” blending mode.

Once the stacking work is done you have finished the lion’s share of the process. All that is left to work on is the landscape (non-sky) portion of your photograph. During a 2 hour stacking set, the moon will move across your scene. Most often you will find that the moonlight movement has illuminated different portions of your shot. One technique I use is to take parts from several images to get the best overall result. An example of this, is when you start the moonlight will only be on the right side of your scene. Towards the end of the series, the moon will have moved higher in the sky and is casting light on the subject matter on the left of your scene which earlier was only in shadow. You will also want to hunt through the images to find the ones with the least amount of motion blur on trees or bushes.

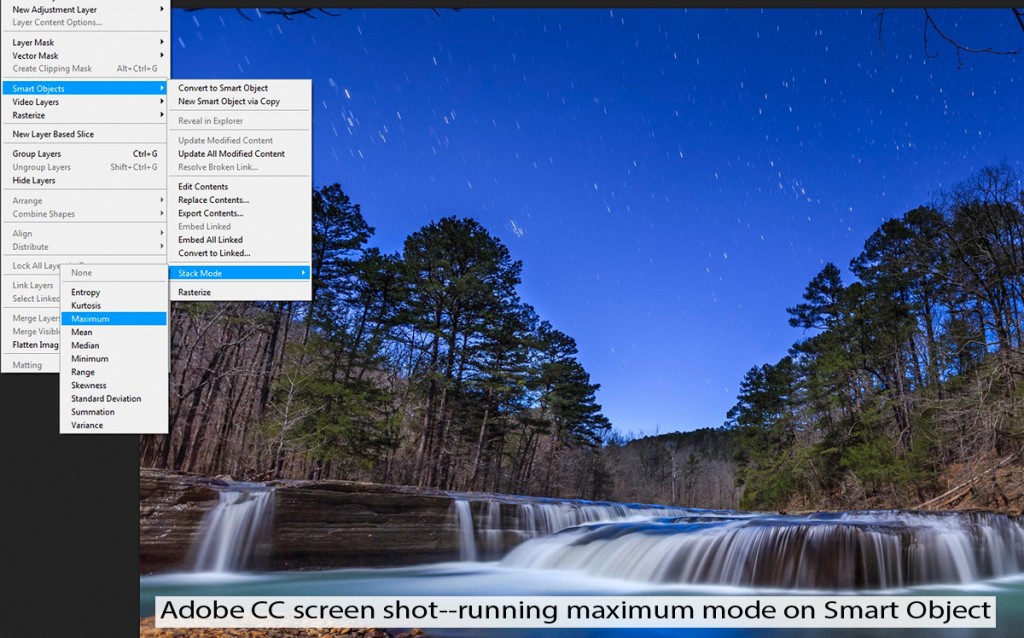

Stacking does introduce faint gaps between each exposure. After you have run the blending modes and combined the files, you can see the faint gaps created between the exposures. If you happened to stop the camera to check a file or move a flare buster to a new position, you will have an even longer gap. These gaps do detract from the star trails as they break up the continuous flow of light you are attempting to capture.

In this crop taken from the sky after the blending modes have been run, the small gaps between the segments can be seen along with larger gaps created by my stopping the process briefly to check the exposure balance.

I have found that the easiest way to remove the gaps, is by using software called “Star Tracer”. Star Tracer is a stand-alone Windows based software. There currently is not a MAC version. Star Tracer uses some pretty advanced algorithms to move the image forwards and backwards to adjust the existing trails over the gaps, thus closing them. I feel that closing that gaps makes for a much more appealing final image. Star Tracer comes with a nice help section and is pretty straight forward to use. The most critical data is making sure the FOV (Field of View) of your lens has been inputted correctly into Star Tracer before you run it.

In this crop, of the same image after I have run Star Tracer you can clearly see how the various gaps have been closed, giving the final image a much more pleasing look.

The end result will have an amazing amount of detail for a photograph taken during the black of night and I feel much more pleasing to the eye. With stacking you can create images that will appear as if they were taken in daylight, in fact many people will try to tell you that the final images are combinations of daytime and nighttime exposures. Of course that is not true and all they have to do is go out and try it. One of most fascinating aspects of this process to me is just how light is available when the correct exposure/aperture sequence is determined. There is more work involved, but the final image that can be produced is more than worth the effort.

D800 Reticulation issues during night photography–white dot problems

- At August 02, 2013

- By paul

- In Articles/Reviews, Nikon Gear

0

0

I have been using the Nikon D800e now for about 10 months in outdoor night photographic work. Recently I have noticed a disturbing issue with the results which I believe look very much like reticulation errors from the old darkroom days. If you over processed a B&W negative during the you could get a coating of very faint white dots on the negative. You can also sometimes get this in the print making but I found it more common on the film processing side. The net result was a ruined image that was covered in white dots. So far in my years working with digital files I have not seen this type of an error. With the D800e I noticed some a few white spots on some of my longer exposures when I first started to use the camera for night work. However they were not very numerous usually only numbering from 10 to 20 total. On my last night outing my D800 really had a problem with this. When you double click on the image shown above you can clearly see the numerous white dots throughout the image.

A bit of history, my night photographic work is done with stacking. I prefer the output from stacking over one single long exposure. If you work with a Nikon on a single long exposure with “long exposure noise reduction” turned on, there is a problem. Nikon like all other camera companies, basically runs a dark frame for the same time as the original exposure. However with Nikon you are locked out of the camera for the duration of the dark frame. So if you shoot a 45 minute single exposure, then after the original shot finishes, you will then have to wait another 45 minutes while the dark frame runs. You cannot take any other pictures or make camera adjustments until the dark frame finished. There appears not to be a buffer that the dark frame can be run in the background. With Canon (at least on the 5D MKII and 5D MKIII) you are not locked out and the dark frame is done in the background in a buffer. You will eventually buffer out after about 3 exposures, where on the 3rd shot you will have to wait for about 20 minutes for the camera to free up, but this is still much better than Nikon’s implementation which is the same as Phase One’s on their medium format backs. I always recommend long noise reduction to be on with single long exposures as there tends to be way too many stuck pixels created and the dark frame will remove these along with some of the base line noise created.

In night photographic stacking where I am shooting to create star trails, dark frame noise reduction creates way too many gaps. An example during a a series of 1 minute 50 second exposures where I might take 25 total frames to get to around 45 minutes I will have only 12.5 total frames of data, the other 12.5 frames will be taken up during the dark frame. Yes there are tools like Star tracer to fix the gaps but to fix this many large gaps really causes some overall problems putting the final image back together since Star Tracer has to really move the file to close the gaps.

When a digital camera gets hot you start to see strong image depredation. With Canon files this seems to show in dark black splotches that can become way to numerous to remove. Traditional dark frame subtraction will not get these out since they are already black. Dark frame subtraction is looking for solid colors (red, green and blue) from stuck pixels, and large areas of noise. So in the past before I started to stack my exposures, once I started to see the black splotches on my images I tended to stop for the night. In Arkansas, where summer temperatures can get 8o to 85 degrees at midnight with high humidity you are limited to just how much your camera can handle. Because of this I prefer the wintertime, fall or springtime to get in most of my work. But it’s still hard to resist a clear night in July and August.

With the Nikon D800e you are taking a file that is approximately 2x larger than the output from either a Canon 6D or 5D MKII, even a 5D MKIII. Canon also offers the small and medium raw output which I often use. The reason being that in night work you are not as concerned about the finest details. I would love to see Nikon offer at least a medium raw size output on their their D800 family of cameras in a firmware update. A medium raw output would be around 20mp in size from the D800 and you might not work the chip as hard as with a full resolution output.

As I mentioned earlier when I first started to shoot with the D800e at night I would always see just a few solid white dots. Never more than 20 and usually around 10. These dots were the size of a normal stuck pixel and easy to remove. Lightroom which normally does a good job at removing stuck colored pixels ignores these however and I had to go into the file and manually remove the. I did notice a slow increase in the numbers of these “stuck” white pixels but they were never a big deal. On my last night shoot with the D800e I did start so see many hundreds of smaller white dots. They were about half the size of the stuck pixels sized dots but way more numerous. You could see them on a 100% review of the image on the LCD of the D800e. When I returned to my studio and started to work on the files I found that these white dots numbered more in the thousands. Way too many to manually remove.

The dots are small and faint but depending on the conditions where you shot the stars but if you are stacking then they really pose a big problem. This is because with all stacking, you tend to get faint gaps between the start trails. The gaps can become larger, if you briefly stop the stacking process to check your exposure. On a 45 minute or longer stacking series, I will tend to stop the camera several times to check my exposures to make sure for example the moon has not started to create destructive flare, or due to the amount of moonlight I need to increase or decrease my shutter speed/iso setting. To close up the gaps, I use a software tool call Star Tracer and it does a great job. However the way it closes the gaps is to move the image up and down slightly and by this it moves the star trails over the gaps closing them. If you have dots or stuck pixels, you will see the dots take on a stepping pattern the number of steps is determined by how many times star tracer had to move the actual file. This creates a dotted line throughout the image and can ruin the image. The only way to fix it is to manually remove as many of the dots as possible before you run Star Tracer. Here is a closer view of the problem areas in one of my shots.

After first seeing this, I found that I could remove about 1/2 of the problem dots by increasing the amount of noise reduction I was using on the file. In Lightroom I increased the noise detail slider, the color noise slider and the overall luminance slider. This in effect blurs the dots enough many of the more faint ones will not show up. Since I also stack the images in Photoshop I run both a maximum and mean stack mode and then combine the two. By combining these outputs you can reduce the number of dots by as much as 1/3 more. I also have found that by using Capture One instead of Lightroom I can remove almost all of the dots since Capture One has a different noise algorithm which seems a bit more sensitive to this type of problem. Capture One also offers “single pixel noise reduction”.

I also ran the same D800 Raw files through Capture One version 7 and with the single pixel noise reduction slider moved to about 50 percent these dots are almost all removed. On this particular shot the moonlight was also causing a similar issue that one sees when using a circular polarizer. The lens I was using was the Nikon 14-24 @ F3.5 and the sky consistently was darker in the center than on the sides. This is not classic vignetting, as the amount of light and dark areas far exceeded normal vignetting. Here is a small shot from a Capture One processed image.

Capture one actually processed out the files quite a bit easier than Lightroom 4.4. I tend to still lead with Lightroom 4.4 with my D800 shots especially the night shots. This due to the fact that Capture One tends to have a bit more problems with the blue hue of the night sky which is due to the moonlight. Capture one does apply a bit more noise reduction to the files than Lightroom as a default. This will generate a very clean sky, but tends to make trees and rocks a bit tool soft. This is not really a big issue since I am stacking and generally only will use one image’s foreground for the final output. It’s very easy to go back and reduce the amount of noise reduction and then re-output the file. On these images where I was working with about a 4/5’s moon, Capture One was able to pull out quite a bit more of the distant stars than Lightroom. Here is an side by side showing the difference the noise reduction settings can have on the more detailed parts of files in Capture One.

I am hoping that this issue does not get worse, as if it does I will have to send the camera back to Nikon to see if they can determine what might be causing the problem. So far I have only seen this type of noise in my night shots, however they seem to show up even in the lower iso ranges of 200 through 400. As I only own the (1) D800, I can’t state that this is an issue with all Nikon designs or if it’s just an issue with my D800e or all D800e/D800 cameras. In May when I last shot the D800e at night the ambient temperatures were about 82 to 75 degrees which should not be that much of an issue. I would expect this more in temperatures of around 87 to 96 degrees.

The other option would be to try the D800 on a single long exposure with the long noise reduction on. This would limit me to about only one shot per night, maybe 2. Or I might try to stack with the long noise reduction on and see if I can get Star tracer to close up the gaps. Either way it’s a major inconvenience.

Equipment in Use–Nikon MB-D12 Grip for D800

- At July 20, 2012

- By paul

- In Articles/Reviews, Nikon Gear

0

0

- Nikon MD-B12 installed on the Bottom of a NIkon D800

- Nikon MD-B12 grip with L bracket installed

- A breakout of the battery holders for the Nikon MD-B12

Click on any of the thumbnails for a larger view of the image.

Since I purchased my Nikon D800, I have added the new Nikon MB-D12 battery grip. I am planning to write a full review of the grip in use with the D800, but this is a quick view of the grip. The pictures show the grip installed on a Nikon D800, the various battery holders that come with the grip and the grip and an L bracket. Overall the grip is nice addition to the D800 and with it installed you gain quite a bit of extra run time by using either another Nikon battery or a series of 8 AA batteries. It’s a nice feature to be able to use AA batteries as if you are in the field/remote parts of the United States, you can almost always find somewhere to purchase AA batteries. Also if you used the energizer AA lithium AA batteries, you may be able to last for 3 to 4 days without having to change out the cells.

There now appear to be several clones available for this product costing hundreds of dollars less. You can find both of them along with the NIkon MB-D12 on Amazon.com The early reviews are that both the clone grips seem to have similar build quality to the Nikon MB-D12.

From my daily usage I have found that the MB-D12 adds a good deal of heft to the entire D800 camera when carried. The grip is rather wide at the bottom, considerable wider than the build in grip in the higher end Nikon D4. When you add a L bracket like the one from Really Right Stuff, the camera, Grip, AA batteries, and L bracket with a Nikon 14-24 lens mounted are close to around 5 lb. total weight. I have not yet tried the standard Nikon Lithium battery in the grip yet, but it will have a bit less weight than 8 AA Ni-Mh cells. I was able to use a Nikon D4 for a few days and the weight/heft of the D4 is much more manageable however at a much higher price point with considerably less pixels. The run time with both the internal Nikon Lithium battery and the batteries in the grip allows for a tremendous amount of shots and review of those shots. It also makes the use of live view in the field a bit more manageable since with only one battery installed live view seems to drain the camera pretty quickly.